Come on in and take a gander-

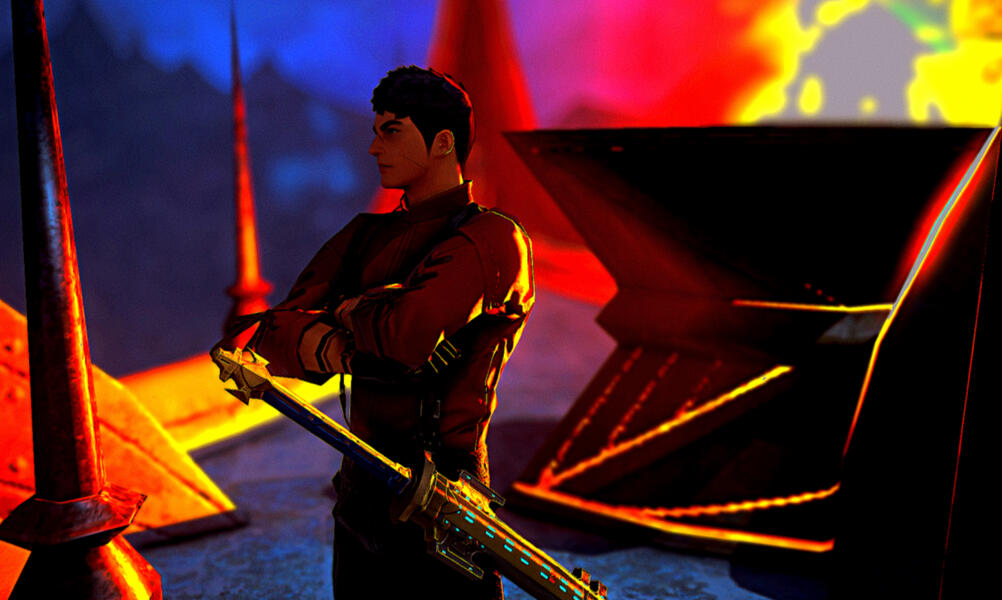

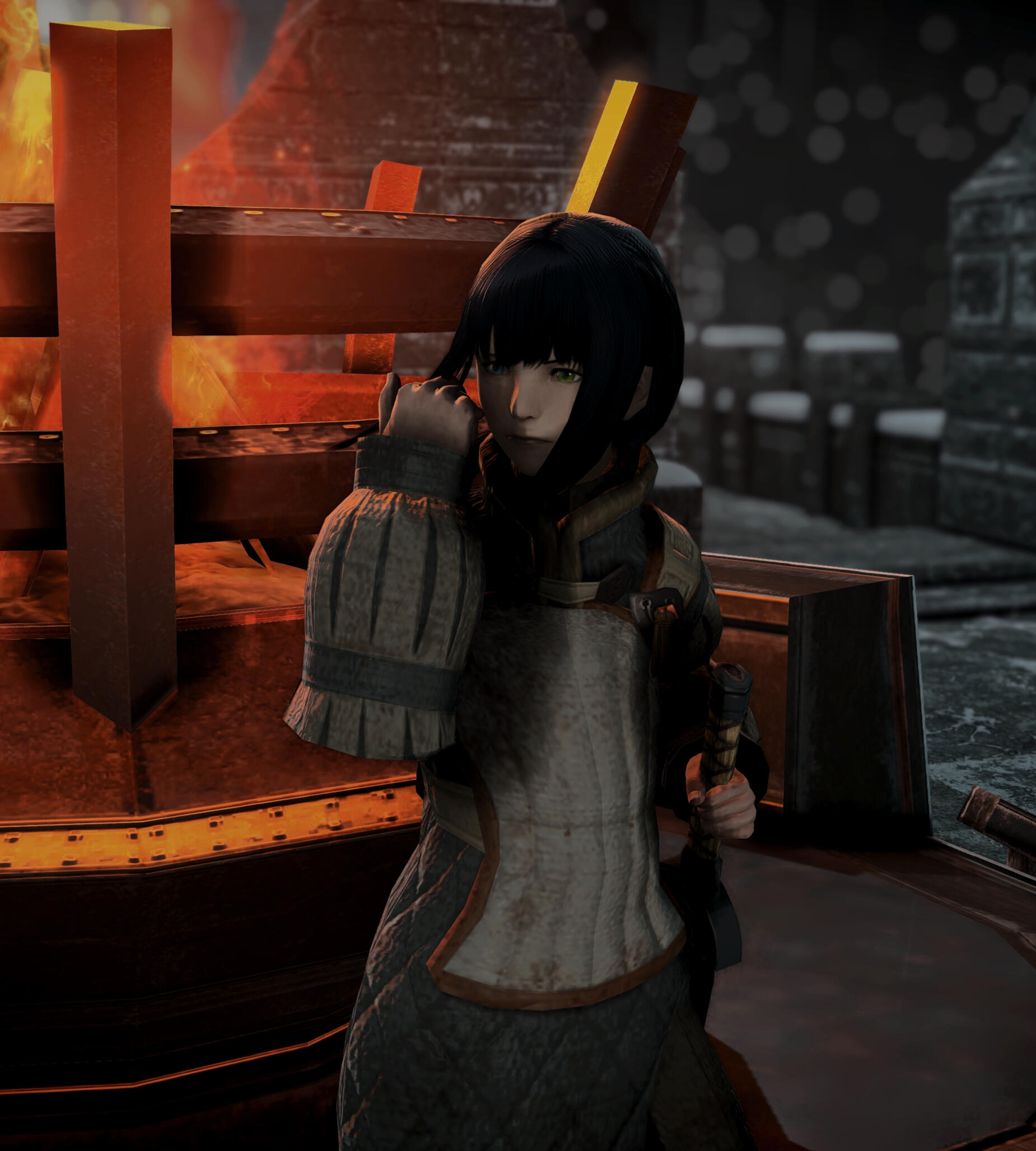

| Name: | Noyel Oszkar |

| Race: | Midlander (Hyur) |

| Age: | 29 y.o. |

| Profession: | Dastard |

Noyel

☾ Logistician ❅ Dog of War ☽

Afflicted by a paradoxical ennui:

'The fires died, but the heat remains.'

-pay no attention to mischievous slander

♫

"Now there's just an afterimage, a burn on my retina, and the faintest trace of warmth on the metal."

⍤ ❝ ❞

🗒 RP Hooks / Rumors 🖋

🕯 Seeking mercenary work? Rumors abound of an enterprising new Captain forming a sister-company to Oschon's Raiders. Currently operating out of Eorzea, a band of specialists has coalescing to form the core of the newly minted Kingfisher Company.

[IC organization only; no FC]

🕯 -or seeking a mercenary? Whether it be a solitary specialist or a muddle of militant marauders, Noyel can provide, if you flash some silver (or better yet, gold).

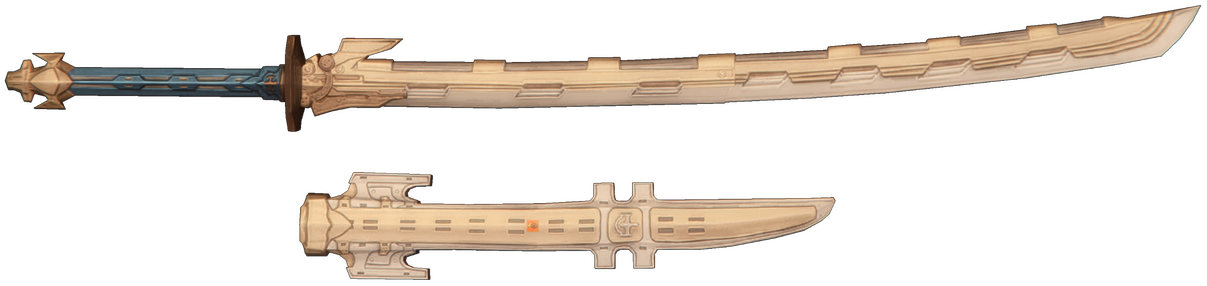

🕯 Well-acquainted with or interested in Red Mages/Crimson Duelists? It's not a skillset oft-displayed, but it seems he's picked up a not-so-academic interest in it from... somewhere. His understanding of the arte could only be graded as passing at best, however, and is merely theoretical.

🕯 A victim, participant, or opponent of post-Calamity Thanalan banditry, or even the slave-trade? You just might recognize him by a certain obscure but disreputable brand, or even by visage alone, and he certainly wasn't on the side of virtue.

🕯 Veteran of the Dragonsong War? Noyel was among the Free Companies that aided in the defense of the Coerthan Highlands during Nidhogg's attack on Ishgard (Patch 2.x). Alas, his logistical skills couldn't contend with the harsh conditions of post-calamity Coerthas and the unparalleled mobility of their enemy, and his company was ultimately stranded at Camp Dragonhead. Later, he was present under Captain Haimrich of Oschon's Raiders for the final battle against Nidhogg—upon the Steps of Faith—that ended the Horde.

🕯 Whether it's the eye or the nose that notices first, the presence of anything sweet will inevitably be sussed out. Indulgent sweets are a weakness of his, and draw him like a bird to the snare of a fowler. He's particularly fond of honey.

Other Themes Of Interest:

Found family, ghosts of the past, survivor's guilt, revenge, how one should go about reforming aspects of a culture or society they don't agree with, political uprisings, the fate of bystanders in war and political conflict, sliding into dark moral grey for noble objectives, military campaigns, economic intrigue, wilderness survival, et al.

☪ To The Moon, Apple of mine eye ☪

Death.

Too young for death.The boy was entirely too young to have to know death in all its facets, she thought, so she told him a lie: “We won’t be able to see each other again, soon.”One outstretched finger, gaunt and trembling, pointed weakly to the full and bright winter moon, two cormorants held within its luminescent eye. “I’m going—far away," she said. "But I’ll always be watching over you.” The boy knew it for a lie immediately, and she knew that he knew.“But-- mum, how'll I bring apples all the way up there?” he asked. Of course he still asked. The long spiral of a peel hung limply from where it met the knife. Errant light from the crepuscular haze bent around uneven panes of glass to catch and cast a small jewel in crimson, the first and last drop of blood from a tiny cut. A small finger strayed too far.“You’ll find a way,” she said. “I know you will.”

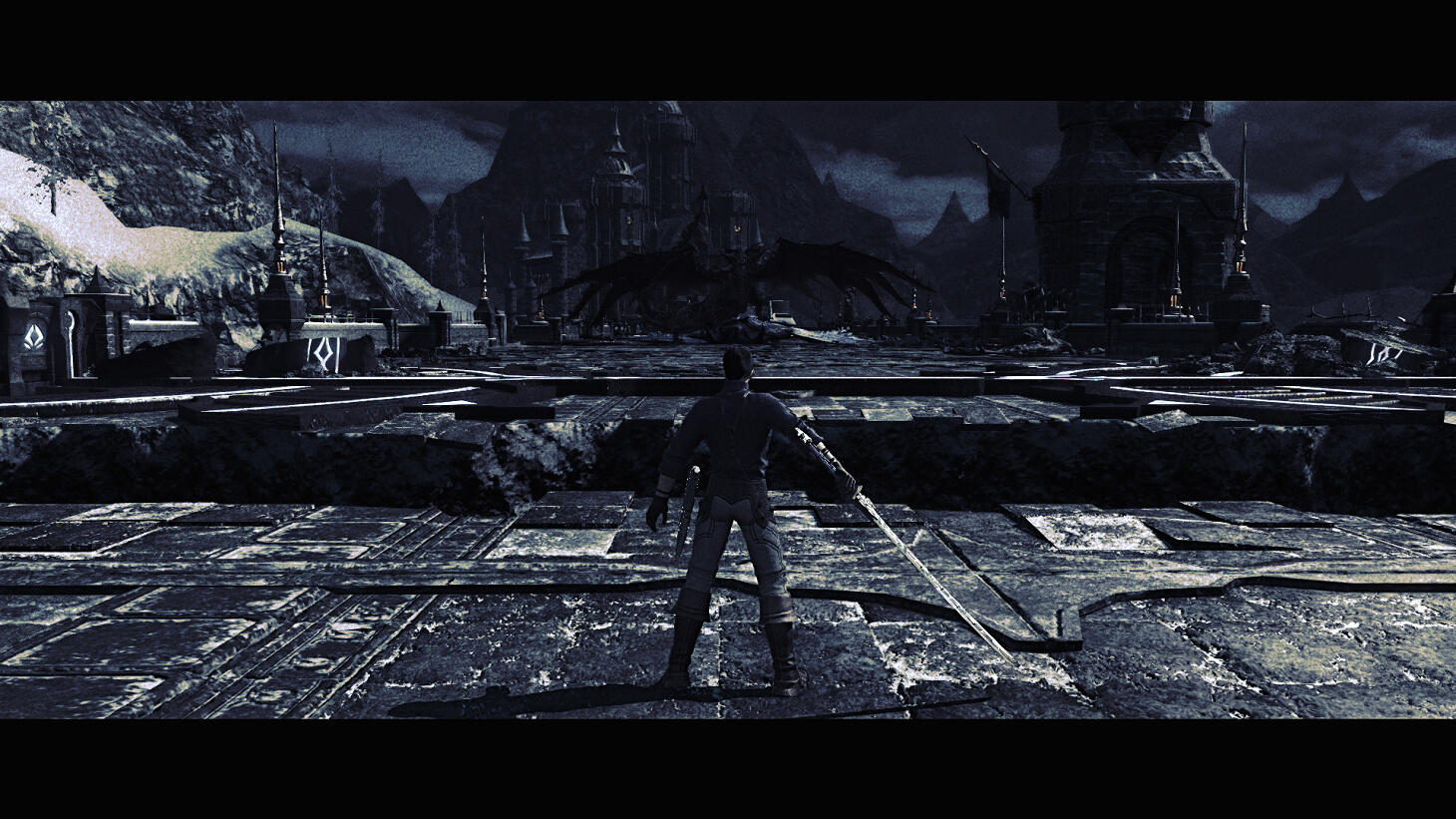

🗡 A Soldier of Fortune and Logistician alike ❂

"That's when I saw her: our 'dark knight.'She was exactly that though, in camp. Kind of a quiet, brooding thing. Till she was up the first ladder that touched the walls. I swear, she got up that thing without using her damned hands. Soon as she'd hit stone she was slinging her halberd around until that section was clear. She swung the wretched thing so hard she broke the shaft, a good ilm and half 'round of solid ash wood, then she beat the last poor sod guarding that stretch to death with it.Later on, I saw her take out three of the heretic governor's armored bodyguards, fellows in just about full harness with, only a longsword. Couldn't even tell how they'd died, except for the trickles of blood leaking out of armpits and visors. And the one missing all his fingers, but not a dent on any of them otherwise. Our very own angel of war, eh?Our 'annointed' knights couldn't fight for shit. Pretty sure they were ninety malms away, back at their fort arguing over who got to molest whose squire. Don't even get me started on the Temple Knights. Just what you get when innumerable stuck up pricks and full metal codpieces are all in one place.Least, that's how I saw it."

Apostate to Garlean exceptionalism

a pragmatic and practiced Dog of War through and through

Born Noyel aan Oszkar, attending the university of Medical Sciences in his administrative region of Garlemald was little more than a pipe dream. Gaining even the slimmest chance of admission, much less acquiring the sizeable endowments and government grants it would require to even hope to attend, was a privilege reserved for citizens.And so it was that this Garlean Hyur joined the VIIth Imperial Legion, his well-developed skills in literacy and administration from his time spent as an assistant scribe to a University hospital Notarius landing him a position as an Architectus, managing supply and logistics.The Battle of Carteneau was a baptism by fire beyond anyone's reckoning, and he was amongst the forces to dig in at Carteneau Flats after the fall of Nael van Darnus and face the Eorzean Alliance.Amongst the scarce few survivors remaining of the Garlean forces, most returned whence they'd come. Noyel, however, scrounged, poached, stole, and murdered his way down to Thanalan, just another refugee amongst a sea of many. At times fighting for bandits-turned-mercenary, the city-state of Ul'dah, or foreign companies, his life as a mercenary began when The Calamity wiped the slate clean.

Et Salamandris Et De Caeteris Spiritibus

There are entire worlds where the light of justice cannot reach. And when heroes fail to act, it is often not for want of valor, but for knowledge that such wickedness exists in the first place.

ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤㅤㅤ ㅤㅤWho may tread there, in their stead?

"All warfare is based on deception."

An elegant demesne perched cliff-side, roused from comatose state to a new clatter of azure arms and bolts by the bucket—like an ant colony crawling amidst flourishing gardens and resplendent halls only to retreat inward come night. By whose authority had such a force assembled?

Surcoats evoke the summer sky in their blues,

splashed with tumbling alabaster cumulus.

Their gilded celatas glittering, resplendent,

mark them out as well-funded and disciplined enough to maintain a shine.Yet for all that elegance in captivating colors lain across freshly polished arm harness and fine cotton coats, why is it that the faces that peer out from beneath those armored brims seem anything but?

Scar-marred faces decorated with habitually reset noses and ill-healed jaws promised violence with their paradoxically empty-and-at-once-focused stares that they might level upon any curious bystanders. These men and women are undeniably steeled, brutalist architecture covered in the thinnest veneer of tinsel and gilt.

Survivors of a Malefick Venome, the deadly push through the isthmus of Ghimlyt, and the generational strife of the Dragonsong brought to an end by a slaying, these hardened hearts gathered are experts in snuffing out the lives of their fellow men, Ixal, and monsters alike.

But a select few among them could recall older conflict yet--More turbid by far.

Come on in and take a gander; pay no attention to mischievous slander.What is there to see but the flare of cannons in the moonlight, belching fire and brimstone in swirling ember hues, the glitter of runners by torchlight and the great flaming balls of fire they'd launch to set ablaze the storehouses and homes? The thundercrack of muskets, an antecedent to the flash that was itself just a precedent to one more missed shot that pinged off of the balustrades.

Much to lose. Even more to gain.

A venerated Vizier

tumbling

into

the

valley,

Devils pushing the flanks,

And beneath it all like fervid undercurrents flowing to the distant sea no longer:

a dry and dusty river.

The Kingfisher Company

— Notice: Skilled soldiers sought ; vaunted valorous veterans valued verily —

Additionally seeking:

- Those skilled in the production, preservation, and procurement of arms and armor—smiths, weapons dealers, and engineers §

- Scouts, spies, and skirmishers §

- Caravaneers and chocobo handlers §

- Camp followers providing cooking, laundering, liquor, nursing, and sutlery services §

*Regular meals, generous pay, and guaranteed pension given for grievous loss of limb incurred in service to The Company are guaranteed to all recruits.

Inquire at the offices of Captain Noyel Oszkar

[IC organization only; no FC]

There is only one Sin...

-Defeat

There is only one Grace...

-Victory

Seek dalliance with dastards

To earnest ends

Amongst maudlin marauders

Lay healing hands

And darker secrets, ensconced in Red

Current Plot:

Ghosts of Yay-ka-ta

Past Plots

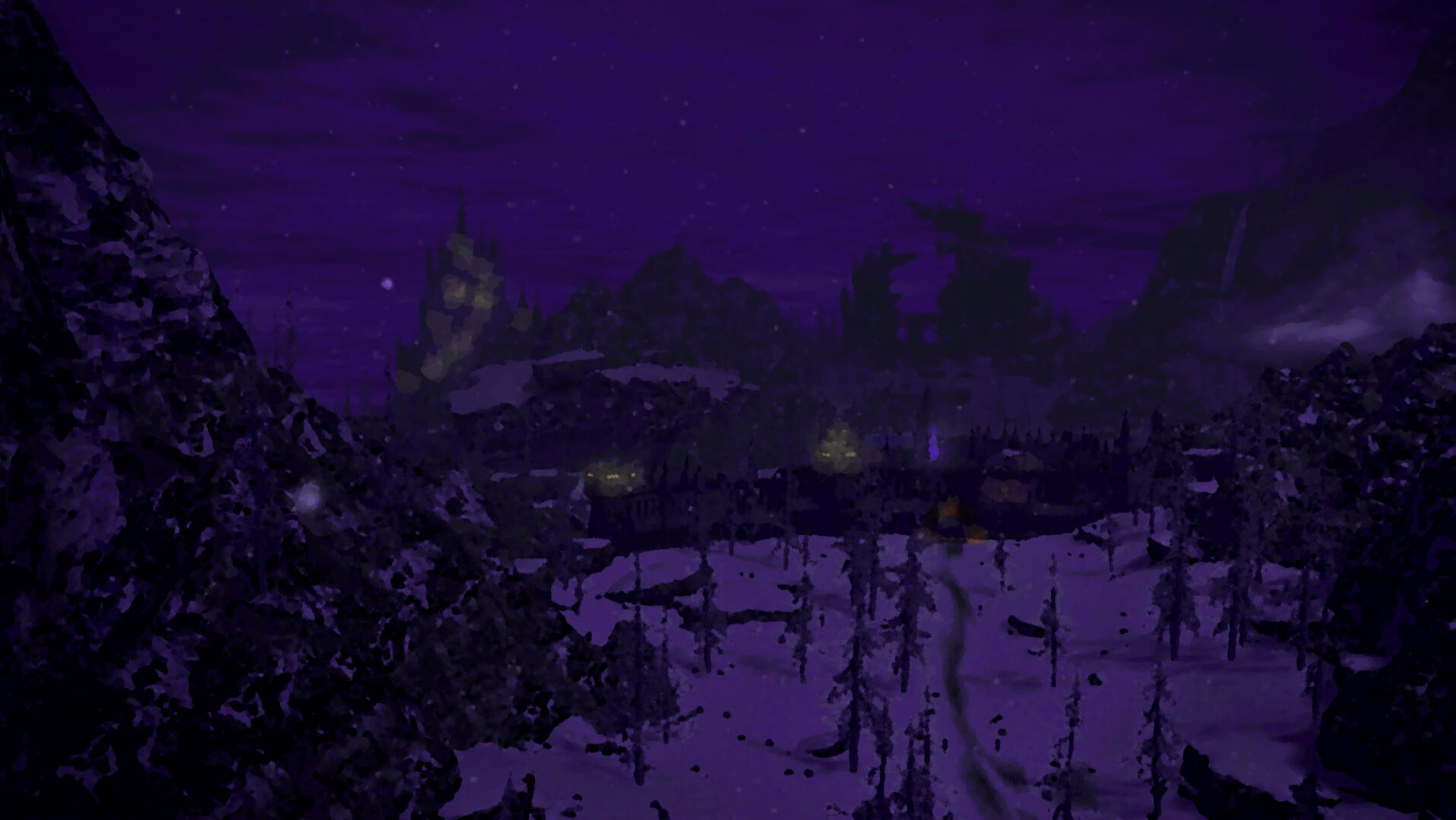

Snowcrawler

(Completed: 12/10/2023 - 6/17/2024)

"A curious place, The North. I'd once thought of it as bearer of the darkest night, and while there is undeniable truth in that, it too hosts the longest day. In short, it is a land of extremes. It figures—that even The Star itself would put in place no half-measures out here. Moons of boundless darkness. Moons of changeless brightness. The year is as disparate as the two sides of the remaining moon, which the astronomers say only ever shows us half its face, hiding unknown forms upon its opposite side, forever dark and unseen. How easy it is to imagine monsters and other foul things making their home there, away from our shining eyes.

And yet there is no comfort in the light here, which causes us such burns of the skin and pain to the eyes as it reflects off the snows that the medici see more cases of those things than even frostbite. For some such possibilities seem beyond the scope of reasoning, beyond the ken of understanding. That is why meticulous preparation and investigation are key. Though, stare into the light for too long and--well... I've never been fond of stating redundancies."-Sestia kir Fairclough; Architectus, Danube Program

The Snowcrawler, a Garlean Mammoth-class polar off-road vehicle, served its eponymous purpose, delivering the party to a secretive facility nestled in the remote mountains of northern Ilsabard. There, a great evil was foiled.

Old Bones Hold No Blood: Prelude

"Blood gets you nothing but more blood. It follows me now, always, like my shadow, and like my shadow I can never be free of it."

Were one to scratch out all their own admissions on tawny pages at the end of their life, what could serve to bridge the gap between pathos and parchment but a paint of vital essence thrumming through their very veins?Blood, after all, doesn’t lie. But neither does it tell the whole truth.Crimson and carmine clotting tenderly in the pen’s nib—why is it that the woeful desert seems intent on swallowing even this?It has seen a venerated Vizier stumble.

It has seen three brothers fall.And beneath it all like fervid undercurrents flowing to the distant sea no longer:

a dry and dusty river.

Those that called themselves paragons or paladins or pearlescent protectors of the precious proletariat are quite quick to proclaim that all life is equal. A pragmatist or a proctor or a procurator of property precepts would be quick to counter that there were many means by which the value of a life could be measured. Priests could certainly be on the fence of this age-old argument, but in the lands of Thanalan where Nald’thal ruled as divine supreme, value was prescribed to everything in this life and the next. The value of this eternal life, therefore, could be measured in this place by the amount given over to the Order of Nald’thal in 'charity'—a state of affairs quite capped by how much worldly wealth one had to give in the first place, coincidentally.And what a grand array of wealth lay before the fine folk of Ul’dah, presented by Ganelon Lannis in as lavish a party as had been seen this year. For one so keyed into the cutthroat world of Thanalan business, he would've certainly had his own views on the valuation of a life. There in the remote estate of a business mogul who seemed to have sunken his chips into every profitable Ul’dahn venture thus far—precious stones, the works of Sunsilk Tapestries, shares in the Platinum Mirage, and even a cut of the newly established stream of Ceruleum coming out of the Legion-held pump stations in Bluefog—a celebration was being held for the recent engagement of his son. Though, in truth, the fellow seemed to host so many parties that this was hardly a notable affair aside from the sheer scale of the festivities this time around. Perhaps this would be like the rest, an opportunity for shadowy business dealings in smoke-filled parlors, or perhaps everyone attending would truly be partaking in the debauchery of the highest class enjoyed by the Ul’dahn elite.As for the group of outsiders that sought entrance into the soiree, who were not truly among the cacophony of dancers, musicians, ‘dancers’, actors, extra servants, and guards hired to perform all the most difficult tasks, though they might pose as any one of these, they had followed the trail of a certain economic exchange. With plenty of less-than-reputable help, Noyel had tracked down an important transaction between Lannis and one Tutuzan Rorozan, another successful merchant, made some years ago. Now, The Captain would lead a crew straight into this den of mummers and vipers, set to play a dangerous game of social manipulation and subterfuge, in order to pull off an ambitious heist.They would aim to steal a most curious prize:

A person.

The Snake and The Flower

One for Luck | One for Power

"Have you yet walked the Halls of The Hellebore? Touched the frayed fringes of the death shroud that forever covers our Lately Queen? Make of my liver the musk and my stomach the ambergris. Brew of my blood the Friar’s Balsam and let my flesh be rose petals. Take from my eyes the purest labdanum and make powder of the Ghostmaw that grows from my skull. The earth breathes through me. I shall descend to the lowest halls and there I shall wait in the darkness, in the veins of the earth. "Even as the Ixal’s Golden Hope, Suzal, lay slain on the battlefield, the rampage of the Deathgazes in the company’s camp was still being contained. Pincushioned by lance and arrow, the starved, enraged beasts had rampaged to the bitter end. The few whose duty it had been to dispatch them in their death throes must have wondered—had the Ixal truly brought them down from Xelphatol? Even more must have pondered how the enemy’s forces had located them so quickly, even after the Captain’s gambit had taken them through a malm of Gelmorran tunnels. The answer, it seemed, resided in the connection between strange things they had seen there and a dispatched Deathgaze that had nested up on the Central Shroud’s Naked Rock. It was the ‘wights who had done it, Noyel seemed to think. He laid claim to the bounty, to settle that last bit of business that saw a steady stream of vicious cloudkin appearing in the skies of the Twelveswood from some unknown place. And so he would lead the rest of them, against their better instinct, to the darkened halls beneath the earth.

An edelweiss cast in gneiss, fear enough to shoo off the midnight mice, and the adder stolen twice.The lily lies, sticky with scarlet, sickly and sweet. Rebirth from strife: is it truly so neat?

Perhaps we're doomed to repeat the same cycles forever—

𝘰𝘷𝘦𝘳 ᵃⁿᵈ 𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫

Government Mandated Misery Affairs

"𝐵𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑘𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑖𝑠 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑒𝑎𝑠𝑦 𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑡. 𝑁𝑜𝑤, 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑚𝑒𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔, 𝑡ℎ𝑎𝑡'𝑠 𝑤ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑒 𝑡ℎ𝑖𝑛𝑔𝑠 𝑔𝑒𝑡 𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑘𝑦. 𝑊ℎ𝑎𝑡 𝑐𝑎𝑛 𝑦𝑜𝑢 𝑑𝑜 𝑤ℎ𝑒𝑛 𝑦𝑜𝑢 𝑠𝑢𝑑𝑑𝑒𝑛𝑙𝑦 𝑓𝑖𝑛𝑑 𝑦𝑜𝑢'𝑣𝑒 ℎ𝑢𝑛𝑔 𝑦𝑜𝑢𝑟 ℎ𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑡 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑠𝑜𝑢𝑙 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑎𝑙𝑙 𝑦𝑜𝑢𝑟 ℎ𝑜𝑝𝑒𝑠 𝑜𝑛 𝑎 𝑠𝑖𝑛𝑔𝑙𝑒 𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑘𝑒𝑡𝑦 𝑝𝑒𝑔 𝑙𝑖𝑘𝑒 𝑎 𝑓𝑜𝑜𝑙?"

The first Garlean engineers must surely have dreamed in cerulean ceruleum, for pale blue ice was all they had ever known, and the azure fire would prove to be their deliverance from it. That, it seemed, was where the tragedies began.For all the horror that the Autumn War and the reign of the Mad King unleashed upon Gyr Abania and the Kingdom of Ala Mhigo that was cradled in its mountainous bosom, they would both pale in comparison to the pain unleashed by Garlean expansion. Whether it be at hands of the White Raven or the Black Wolf, for they had known both well, the Ala Mhigans would suffer doubly for their historical sins. The frighteningly rapid fall of the city-state holding the greatest martial might on all the continent was not the warning sign for the rest of Eorzea that it should have been. Surely they deserved it, countless had thought at the time. But just as easily as hearts had been swayed against vicious mountain men they had never met or even seen that were supposedly hellbent on conquering Gridania through force, so too would they eventually be turned towards helping those same poor refugees fighting for their home. And so it was that the resistance, temporarily united alongside a force encompassing all of the once-hostile city-states, took back their home and drove out the invaders.But what had lain broken for so long would prove not to be so easily mended. The peace of The Empire's inner territories never touched the rebellious lands of the Gyr Abanian mountains, so well-suited for hiding away self-sustaining bands of resistance fighters, refugees, and whoever else saw fit to make lawlessness and that eternal battlefield their home. In truth, even the resistance that had marched side by side into Ala Mhigo to defeat the XIIth legion was composed of countless disparate groups. Perhaps this was a reflection of the insular nature of the Highland Tribes, or perhaps fighting for so long, cut off not only from sharing supplies but from even communicating. And perhaps, for more than a few, the autonomy they had enjoyed as insurgent warbands proved to be much sweeter than the burdens of picking up the pieces of their land and government. In truth, the provisional government of Ala Mhigo was far from perfect, and depending on who was asked, barely even functional.What a perfect place, then, for monsters and beasts to flourish in the spaces between Garlean and Ala Mhigan forces. What a perfect place, too, for those seeking the perfect veil for heinous crimes—those brigands, bandits, and slavers—to blossom. In those days 'freedom-fighter' had proved a convenient label and, frightfully enough, one which was so oft self-adopted with wholesale conviction. With the Garleans banished, however, those things were not destined to magically disappear. Ala Mhigo would not recover in a day. The sins of the past remained to be grappled with, intermingled with the birthing pains of a reborn government. No wonder, then, that the Ala Mhigans retained that chip on their shoulder. It had barely even begun to heal.The Apotheke would soon find themselves entangled in this dizzying web, drawn in by the auspices of one of their number whose roots had been buried the deepest into that chaotic mess of them all. The war had ended, and yet the land remained a battlefield. Hopefully they would not be swallowed. But just as the Ala Mhigans had proven a tenacious people, so too were the invaders and all who had been tempered in that decades-long thunderdome. The Garleans' flying machines had spread their machinations across the entire known world, and as much of their crimson cruor stained the already-red clay as had been shed by the Ala Mhigans at this point. And like those mountain folk so too would it be known, upon the shattering of their whole world, that those born of the frigid ice fields each held their own aspirations once the leash had been thoroughly slipped. Would this land that had just begun its mending once again be the focal point for greed, terror, and the letting of bad blood? Surely it would, promised the pessimists. Such was the fate of all mankind.

Hence, Homeward Hearts

"When we choose our prisons, the claustrophobia vanishes in the tunnel vision."

"This nation cannot heal while Tinolqa's vermin yet hold fast our wings. The people of Gelmorra must pay for their crimes. For the spirit of Garuda and her blessed folk. For the generational animus that they have etched upon our very egos. For our due destiny locked forever in an exosphere we cannot touch. We will reclaim it from atop these peaks—for those wretched, featherless babes that died starving in barren caves and on stilts perched above stony ground that we cannot bury them in—and for those who have given their lives to reclaim what bounties of Tinolqa the Gelmorrans have stolen so that we might yet imitate how our ancestors soared! Their bodies have been given over to the Eternal Winds and born aloft to their rightful home. And so too their spirits we will take with us when, finally, we go to ours."~'Translation' and transcription of a Huatotl Skycaller's rousing speech by a captured Gridanian scholar. Said scholar is thought to have been executed by means of being forcefully tied to a balloon and released from the highest peak of Xelphatol. Perhaps his body still floats out there. Perhaps, ironically, it even reached the fabled Ixali homeland.

Fragmented reports have reached the ears of Gridanian officials astride the backs of reclusive longhunters and homesteaders visiting to bulk up their winter supplies of certain peculiarities occuring in the far northern reaches of The Shroud. Where the craggy foothills of Xelphatol give way to lush forests much less windswept and bitter, the smoke of great fires (and the glow of such at night) can be seen for malms around. The fringes of the Twelveswood are laced with the telltale sound of axes ringing out, biting deep of sylvan flesh. Some claim that the skies are at times thick with swarms of armored, bulbous balloons drifting down from the alpine aerial. Preemptive reports suggest that the Ixal are clearing way for some kind of construction. It is believed to be a forward refueling and repair station to supply their warballoons and dirigibles with fresh airstones and ceruleum vapor. Allowing the establishment of such a location would allow the Ixal to project force across a much larger area, threatening the safety of Gridania itself. With Gridania's forces committed to pushing the front towards Ilsabard, it falls to the domestic policing forces of Gods' Quiver, and the Wood Wailers to a lesser extent, to combat this new threat. These organizations themselves are stretched thin, their ranks scavenged for the best and bravest to replace grevious losses at the isthmus of Ghimlyt and more broadly the efforts of a war with Garlemald that will soon earn the qualifier of "generational." As always, the city-states must turn to outside forces to secure the manpower and expertise necessary to avert disaster.

Malefick Venome unto the Bewitch't

A mysterious disease afflicted the Coerthan Highlands. Absolute ruin was averted, but the truth of the matter may never come to light in polite company.

The end to the generational strife of the Dragonsong War promised an era of renewed peace and prosperity to be found—not in remittance from an enemy triumphed over—but of an ego and industry turned to brighter things than constant skyward vigilance and seeping bitter dread. What this beleaguered realm received however was the dim pallor of hope, given over to new wars and the shadows of old simmerings, and the birthing pains of a novel government. The House of Commons and the House of Lords, both alike in dignity—or perhaps not—in fair Ishgard, where we lay our scene. And indeed—from ancient grudge break to new mutiny, where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.This newfound equilibrium did little to allay the effects of the Calamity that Nael Van Darnus inflicted upon Eorzea. Once-verdant lands given over to the frightful squall of snow and sleet—the creeping tendrils of umbral ice that seemed to overtake the very soil—saw no respite with the departure of bellicose dragonkin, the removal of the Sword of Damocles that had hung heavy astride the hearts of all Ishgardians. Each year the harvest grew poorer: diminished and pathetic cabbages insulated by more and more layers of straw to ward off the freeze. New avenues of hunting and trapping that by necessity were more deeply tapped with each year passing in the wake of the Calamity would take even more time still to develop, and the pursuance of which doubtless exposed the lowliest peasants to the innumerable dangers that stalked the Highlands. It was a far cry from the three-field system, the legumes and wheat and alpine orchards that barely survived, and the moniker of the road that connected Coerthas to the Black Shroud and upon which many Gridanian pelts were imported, the "Furline," laid bare the painful truth that a scarce handful of years does not a generational change make.There is a darkness that hangs over that land, no doubt. The Ixali, a tribe of birdmen plucked of their pinion feathers by devious fate, stage raids from their banishment in Xelphatol's Natalan and by means of wandering bands that emerge from The Shroud to find new lumber for their dear Garuda. Those highland winter wolves, proving perhaps smarter even than those who walk upon two legs—for how easily they had adapted to their new and much more literate food sources—descend from snow-dusted dens to drag away groomsmen and washerwomen in the night. Had Ishgard's pastoral proclivities been preserved in full through the bitter chill, doubtless their chocobos, pigs, and cattle would have fallen prey in greater numbers to this new breed of predator. Remaining unmentioned are the wandering ever-hungry cyclopes, the dreaded denizens of the the fallen Dzemael Darkhold, and innumerable other horrors that stalk the snowstorms.When one would set foot upon the heartland of Ishgard, the Central Highlands, what would they see but malms and malms of snow and muck and ice and white in fifty-one shades. Doubtless the frightful finger of a forested land gone all hyperborean and ever-wintry would lodge itself like a dagger in the hearts of any who had never been—or managed to escape that place for more than a day—a fierce reminder that their warm and vital blood that pumped unseen through vital hearts could so easily be frozen to a darkened carmine slurry.It was this climate—those dangers—that made the success of their mission all the more tenuous. How could they help the sick, if the three layers of blankets needed to insulate a body that fought against itself must be brought from abroad across that landscape and pass over and by the pitiful lowborn as they eked out their living? From where would herbs to stave off nausea and relieve their painful aches be sourced, if it was all covered in a thin veneer of frost? And besides, even within those walls, next to the braziers and hearthfires, all was far from well. For it is when one is sorely tested that their true character is revealed. Icy soil gives way to icy hearts, a vengeful frigidity that not even the heartiest parsnip soup could breach. Investigating the stretches beyond those walls would prove an equal match in frustration and danger. Where would they even begin to unravel this great mystery? What lay ahead were more questions than answers, and an expedition half slap-dash, half desperation, and a plan made on the very cusp. Scarce clues. And that place. That dreadful place, where gold doth glimmer. What answers would it hold in its shimmering, resplendent abyss? Gilt, guilt, fair flaxen fell fears, an edelweiss cast in gneiss, fear enough to shoo off the midnight mice, a handful of perils half-uncovered and four-fifths best left to lie.Yet, still. Still they had come.

That Hideous Strength

That terrible heat. Those words of Maho's that had like talons of molten steel tugged at organs he didn't know he even had. His pupils had drawn down to pinpricks to ward off the flash of the fire and still it hadn't been enough to defeat the birth of the now seared image of lately living morbol upon the backs of his eyes. The vacuum left behind when the sinister spell had burnt all of the oxygen in front of him collapsed with a clap, seizing from his lungs what breath he had held as he gritted teeth against the morbol's onslaught with only a knife and suit of steel. What he sucked into heaving lungs to replace it seared tender flesh, making it abundantly clear that what energy laced the space filled up by the echo of fell magics was not meant to be breathed. And yet before the threat of Gold Lung, of being crushed like a tin can by tendrils or that gaping maw to release but the slightest hiss of vital breath upon collapse, it merely tickled.Nonetheless, his body sought to expel it, and how curious a morphology his diaphragm adopted—his chest and his windpipes, his mind and his heart—as that first shuddering exhale took the form of a strange giggle. And what could the body itself do at the sudden end of a fight when veins still thrummed with adrenaline but take another desperate breath for want of oxygen? This one too stung, and begged for release. The escape of it was like the bark of a laugh, signalling that the cycle set into motion would not soon abate. Soon he was howling with laughter as his body begged for oxygen, tasted deeply of air it cared not for, and never learned its lesson. He fell onto his back—alive—as the now slain morbol released what tension it had held on its end in their tug of war. He laughed his lungs ragged as he tasted, over and over--Ash, thick and cloying. The burnt copper of boiled blood. He had barely registered the back of his head striking the ground in the face of the wave of heat that had washed over him. Whatever the projectile had been, it certainly hadn't come from their side. It seemed to have merely clipped him, because when he turned his head he saw Lockie on his knees screaming, the flesh of his right arm bubbling and sloughing off from the heat of an intense flame."On your feet, oh fearless Legatus!"A pair of hard metal gauntlets dug into the relatively softer gambeson that lined his underarms, pulling him to his knees with a force they lacked on their own. Noyel glanced over his shoulder at whom had laid hands upon him, gaze sweeping first across the block of legionaries fanned out behind him, some scattered on the ground but most just milling around in crimson dust. At the conclusion of his slow arc he found himself meeting blue eyes through the steel cage of a visor recently flipped down. Little good it seemed to have done—or too little too late perhaps—for the ruins of the man's helmet upon the right side laid bare the fact that his whole ear or more had been torn off. Perhaps that was why he was yelling so loudly from such a close distance, but Noyel was glad for the forcefulness of it over the din of explosions and ignoble death—the bark of guns and whip-crack of slung spells."You're supposed to be leading this sorry lot," the man yelled. It was technically true, though the title heaped upon him was mostly a mockery. He hoped. It was true that as that terrible moon had descended and the Eorzean horde had closed in, not a single soldier that outranked the lowly Architectus he was could be scrounged up in the vicinity. Perish the thought; it thus seemed that nobody was even left alive to record what ranks he had obtained by virtue of field promotion either. Noyel's reverie was broken as the man's hand passed low over his long, thin blade, a kaboom much closer to bloodied and abused eardrums than the constant sonorous rumble of distant explosions erupting from it to send some invisible mass of lead hurtling towards their enemy. The man spun about him, waving the smoking barrel of a sword he held with a cry of, "Van Darnus! Van Darnus!" He rushed headlong into the dissipating smoke, followed by a mob of men trailing ragged crimson surcoats.Noyel gave a great, heaving cough as he pushed himself to his feet, tingling fingers scrabbling for his dropped saber. Stumbling round to address his men, he rested his own sword on his trembling shoulder. Meeting the gaze of a hundred legionaries, covered in soot and wide-eyed with shock, he failed utterly to rustle up some similarly heroic words.“Well, fucking come on then, eh?” he shouted over the screams of burning men and exploding fireballs. Thick clouds of smoke rolled over Noyel, filling his mouth with the taste of charcoal, and his nostrils with the smell of burning flesh—two things he was all too familiar with by then. As he squinted through stinging eyes and jogged through the thick white smoke, he lowered his own visor. The world fell away into white and muted shuffling, and he hoped that his men would be able to keep sight of him. But soon enough a great gust of wind dashed apart the banks of smoke and Noyels’ vision was filled with the anemic motes of swirling cinders, revealing the hill which they had begun to climb. He fell in line with the rush of bodies sprinting both to take that ground and to wreak a terrible vengeance upon the unit of spellcasters that topped it. Above, the very sky burned with the broiling fury of the scarlet lesser moon. It utterly dwarfed the massive fireball those Eorzean thaumaturges were constructing, each one sending a tendril of their own channeled flame until they, together, controlled a writhing mass of fire meant to wipe out him and everyone nearby. They had to take the hill before that could happen or they would all suffer Lockie's fate. But before those mages could release it, the moon fell apart.Noyel watched one of the thaumaturges collapse upon releasing a great arc of lightning, as though a marionette whose strings had been cut. Perhaps they'd been hit by any of the near-invisible projectiles zipping across the battlefield, or perhaps they had simply exhausted themselves to the point of total bodily failure. Regardless, they were one of the lucky ones; they didn't have the chance to see what was coming and despair. Despite the fact that the shards of the shattered scarlet moon seemed to fall faster than gravity should have allowed, that distance they had to travel—it left plenty of moments for desperate axons to try and work out how they might dodge a great comet the size of an entire castrum and for those same neurons to come to the conclusion that they couldn't. Dalamud's pieces left great blazing trails upon the sky as they were cast and curved seemingly at random. It was one such piece that landed upon the far side of the hill he meant to climb—that sent shockwaves so immediate and so powerful that it seemed as though by magic his feet were no longer in contact with the ground.The fact that he had not yet crested the peak—that he'd failed in leading the charge to wipe out the thaumaturges—it saved him. The great conflagration rolled up and off the south side of the hill like a rushing tide on a ramp, flames carrying with it great chunks of tumbling jagged crystal that shore apart any who hadn't been vaporized. And just like that, the tiniest fragment of Dalamud had achieved in record time Noyel's objective—a fact that he recognized when, on the cusp of falling backwards down that slope, he noticed that the top few yalms of the hilltop had ceased to exist. Once more he found himself tumbling onto his back, though through serendipity and the cant of the slope he found his feet before he had moved too far.The heavens had fallen—were falling. This was abundantly clear to Noyel as he steadied himself amongst swirling crimson dust clouds independently born from epicenters of impact. Missiles dwarfing the most vicious Garlean artillery as well as the most powerful battle magic he'd ever seen rained down in their multitudes upon the battlefield. The fight was over, the efforts of both sides made irrelevant by the present reality. Those with their wits and bodies whole, Garlean and Eorzean alike, had begun to flee in every direction—and yet none seemed safe. The swell of fire—of the wake of flame, of fear that soaked into all of his bones—the icy hand of an intimate lover, though he burned, tracing the curve of his spine. Fear, always, born of the eventuality of doing what he had not done, counting regret upon hope in anticipation of a last battle. He chose a direction at random, beginning to run perpendicular to the slope of the hill, passing pieces of Dalamud and soldiers alike though he barely saw either.Yet Noyel knew the man he nearly stumbled upon before he reached him by the damage to his helmet and that Garlean gunblade. Contrary to the swiftness with which that fervent legionary dashed ahead before, he was now prone. Far from merely the effects of having been thrown by the explosion, he remained as such due largely to the fact that his entire left leg had disappeared below the thigh. Was it a desire to pay back the helping hand he had been given earlier? An instinctive reaction to assist a fellow legionary? Or was it simply the necessity to confirm that the present shattering of reality was not some delusion with another? Regardless, he found his legs carrying him to the fallen soldier, who was writhing, perhaps in his shocked death throes.Noyel failed to block the desperate blow haphazardly aimed at his ankle with the tip of his saber, numb fingers failing to hold the blade steady against the man's flailing. The strike bit into his boot as he fell, tumbling down onto the man and seizing him by a pinched handful of his tabard just below the armpits. As Noyel peered through that steel cage at those blue eyes, he found only one wide and alert, the other made milky by the conflagration."It's me!" He asserted. This time he was the one yelling into the other man's face, hands trying to provide a steady hold. "It's me! Stop struggling, calm down!" But what was he to do? Heft the man in full, in all that armor, up upon his shoulder? Noyel barely felt he had the strength to stand. It seemed more likely that they'd both have to clutch each other and tumble in a roll down the hill, but that strategy certainly wouldn't help either of their chances of survival, and the remains of that leg least of all. It was then that he noticed that that wide eye was not looking at him at all; nor was it drawn to a vacant thousand yard stare. It was fixated upon a very specific something as it gazed at the sky where the moon had been. It should have been impossible to make out—to put a form to that hazy shape malms away in the sky reflected in the tiny imperfect mirror of that wide pupil. Even illuminated as it was by the new scarlet sun that seemed to have been born from the shell of the moon that still shed its pieces, the image of what was revealed must have been no larger than a pen's nib to Noyel. And yet somehow he knew. He knew it.The Wyrm.Even as another shard of flaming rock a hundred yalms wide burrowed a crater somewhere off to their left, washing them anew in frightful heat and vibrations enough to hide the thundering birthing pains of Menphina's Loyal Hound, he was aware of the sharp intake of breath the dying man took. It almost seemed a death rattle, and yet it gave birth to something entirely unexpected. Noyel felt the warmth of bloody flecks splattered upon his cheek as that intake of breath pushed out ragged laughter. The presence of mind to even insist upon such platitudes as, 'save your breath,' had left him entirely. There was only that ragged howling of strange amusement before him, the deathly heat of the battlefield, the sting of a thousand tiny cuts from where he'd scraped the ground so many times and been peppered by fragments of the falling moon, and the dreadful presence of all their dooms. Noyel meant what passed his lips next to be a question of that dying man's sanity, of some sought confirmation that though the world had gone mad, he was still relatively sound. And yet what slipped forth was a giggle. Even as it became peeling laughter he found that the man he clung to had ceased moving, maw as wide as those eyes, one blazing blue and one milky, as his final death mask.The man was dead. Had infected him with his laughter before expiring. And so Noyel ran once more, lungs strained to the limit by his desperate sprinting, the oppressive heat, and his body's devotion to ceaseless cackling. He tumbled down, down into a gully—some pit carved out by a Garlean shell. The sky had cracked open, red as it ever had been, pouring fury down on the site of their now pointless battle. He fell onto his back—alive—as justice was done, though the heavens fell. He laughed his lungs ragged as he tasted, over and over--

Unspoken

~ Bright red droplets hit the canvas to the rhythm of my beating heart. Two thumps at a time, the gaudy crimson overtakes the flat brown in slowly spreading splotches. It's being ruined, I can tell, by my trembling arm. And that just won't do. I drop my brush and plunge my hands into the rather baroque burnished bronze basin and bring them up onto the canvas, swirling patterns all the while. I can't find it, and the screaming certainly isn't helping. I turn and strike the woman again, coursing rivulets running down her torso and trickling through her sticky, matted hair and spilling into the basin below. This is the third time I've done this, but the screeching does not abate."Dear Kasimir, this sight is quite a fright," Leila says from her perch in the corner of the room. Her stool has only three legs, and she seems to take great delight in the minute swaying that comes from her incessant rocking. "She might misconstrue the true you!"I turn to the hanging woman and give her a gentle shove. Her glassy eyes stare blankly ahead, and I find it odd that her slack jaw hasn't moved since I first struck her."Dear Leila," I say, "I know you only rhyme when you lie."The room is dimly lit, and the scant rays of light piercing the beige curtains hold the wafting dust like a shiny ceramic cast mosaic. I watch Leila spring from her stool and stride over to the one window in the room. The sway of her hips catches my eye like a fowler's snare and they trace her path to my right where she stands with a hand on her waist, ready to admonish me."Would it kill you to let a little light in?" Leila says. The opening curtains kick up a miniature dust devil over the dark brown hardwood counter. "Or to dust every once in a while?"The light seems to dance between each jar sitting there, cast about haphazardly by the curved crystal. I shield my eyes with my off hand as I pick up a new jar of brushes with the other. Just a few careful steps around the spillage brings me back to my seat before the canvas. The screaming still hasn't stopped, but the hanging woman's mouth is quite closed. It must not be her, but I hear it screaming, pounding on the curvature of my skull like her fists had thumped softly against my chest. Her hair was auburn and smelled of lilac as I had rested my chin on her head and strangled her."She looks like you," I remark to Leila."They all do," she says, her voice a soft whisper that caresses my left ear. I can feel her hot breath on my neck as she traces a finger down my arm. I turn to catch her by the hem of her skirt, but she's filling a large bag with dark grey rocks now on the other side of the room. It's strange; I'm not even done working. It's hard to concentrate with all of the noise, but I persist and turn back to the canvas and the hanging woman.The screaming must be coming from some veins yet unlet. The truth is in the blood. It has to be. My knife flenses her flesh, opening countless tiny cuts all over her body. She's grinning now, the loose flesh of her lips hanging limply, at odds with the bloody tears falling from the torn corners of her eyes. I plunge my hands into the basin and bring them up to the canvas. The blood is tepid now, but it's thick and easily sticks to the swirling patterns I trace out. Where is it? I can't find it."Would it kill you to let a little light in?" Leila asks as she slowly swings back and forth, bound by her ankles over the basin."I'm sorry I killed you," I say."Dear Kasimir, that's a quote quite out of nowhere, out of the blue, out of left field for a genuine gentleman, quite affrighted at the benighted thought of harming a fly; you ought naught trot out such a crackpot lie.""What interesting prose," I say, "You must be quite mad."“Quite mad," she says."Don't worry, I'll find out what happened," I say, my caress leaving a few red smudges on her pale cheek. "The truth is in the blood."I trace out each detail in crimson: her hips, the soft curvature of her nose, her sprightly gait, like she had shown me so many times before. She had spun once, then twice, and alighted before me on the shores of the lake. It was going to be a boy, she had told me. I never questioned how she knew, that's just how she was. It saddens me to think that I'll never share the joys of painting with progeny as a preeminently proficient progenitor."The awful cost of all we've lost," she says. From behind her lowered visage, I felt that the corner of her mouth had turned upward. "I'm bad for you.""I'm mad for you."Why? Why her? Why to her? To consider all the blood I've spilled, and to consider on top of that all of the non-answers I've found; it's disappointing. Maybe frustrating. This one would be of no use to me, I can tell. But it's far too late for telling now, with the deed done and the clues all carmine and chalky on my fingertips. This one will have to go into the lake for sure. I put the last of the largest rocks that I had gathered into the bag while Leila watches me from her perch on the stool. It's quite a balancing act--to have her arms wrapped around her knees like that.I wash my hands in a bucket of progressively darker whorls, making sure to clean meticulously under each nail with my small knife. That too comes clean in the little angry lake in the bucket, and I set it out to dry on the counter. With a huff I heft the bag up onto my shoulder. It seems that Leila is already at the door."Where are you going?" I ask. The jagged edge of a rock digs into my shoulder through the canvas. "I've never seen you leave before.""Dear Kasimir," she says, "abstain from feigning clarity; I've seen your blood stained sincerity. Or was insanity that poor pauper's prison you sought, to contain you? There's no more blood to trawl, not out there. Old bones hold no blood." Then she walked out.My numb fingers and limp arms drop the laden sack onto the hardwood floor, which seems to jostle the counter. The knife I placed there is set to a roll and I forget the one lesson my mother taught me: a falling knife has no handle. It stings. As I withdraw my thumb from my mouth, the errant light bending around the jar catches and casts a small jewel in crimson, the last drop of blood from my tiny cut."Ah, there it is." Silence. ~The little novel was closed with a snap, Noyel’s pinky and thumb withdrawn in perfect time to regrasp it in full along the spine, setting it down on the opposite side of his body in the dual shadow of his form and the ledge's architecture.There it was: the first cricket's chirp. It was a signal to the rest of them, it seemed, the hills of Wineport over yonder coming alive with the buzz of cicadas and other critters as the falling sun cast a shadow across the next valley over. The evening's first firefly alighted upon his head, teasing at a stray hair there, although he didn’t notice. His head leaned back further, rolling until it was lain on the corner of the abutment, watching the intruder almost sideways, almost upside-down.Suspicion. Open suspicion flashed across his features in the way the lower lid of his left eye rose more than the right—how the sinking of his brows cast eyes into deeper shadow until they seemed glowing points of reflected menace in the crepuscular smother. But soon enough that visible wariness was buried. Behind him, up on that abutment, his abandoned wine glass was empty—the bottom boundaries of the bowl stained with the dark crimson dregs of a particularly chosen vintage. He grinned.

Eira's Curse

How easily his thumb fell into the gap betwixt leg and arm: a curve that normally would take multiple moments to trace with a full palm and number a good half dozen widths of such placed side by side—that length that held such vital organs as the heart, lungs, and stomach. But it was all too easy even for a young boy to slot his thumb into that space on the crude facsimile of a person that was a clay doll. Why was it that such a thing, without eyes or ears or a nose—without musculature or warmth or hopes or feelings or aspirations—could, with only a moment's glance at the shaped grayish-brown clay, imprint upon one's psyche the concept of a person? Perhaps the mind was just good at making connections with such a shape as the barest outline of mankind. Seeing a face in the knots and burls of a tree, a cloud, or rolling seatide foam doubtless told such a tale of a human mind's attachment to symbolism and pattern recognition.The boy's lips were blueish and trembling, his flesh pale and sallow even against stark white bandages that had been edged out by crimson dried to the essence of clotted iron. Even there in the biting wind, which seemed to threaten snow flurries with its gray clouds, insects were drawn to the cruor as if born spontaneously from the wound, seeking out the radiating warmth of trickling blood that yet dribbled from opened veins beneath those stained bandages. Eira's Curse, given and taken and subdued. No one else would shed the blood for the ritual, so scorned was his sister born blue and silent, though each man and woman, with more liters to spare than a young boy, who turned away threatened the illest omens upon their village as they did so. It wasn't for them, or the prosperity of his village, that he now cradled that crude idol of a person all run through with his blood up to the moors. It was barely even with wishes of peace for a lost soul that had known not a single second of a world that had feared her for not entering it properly. Barely even with a brother's love for his lost sister. He loved her. He hated her. He had looked forward to her coming and now cursed her. It tore him apart. It marched him onward. It was, in fact, to soothe his mother's frightful wailing that hadn't ceased since the midwives had taken that breathless lump in a bloody bindle and tossed it into the sea. To lift the vile auspices that only added to her burdens.Upon cresting the ridge, cloudy breath rolling up and over before he arrived, the boy found himself before Eira herself. She waited upon a rock, half sitting and half leaning upon it, dark hooded cloak draped about her as she watched him silently. The boy's breath caught, the last cloudy puff of climbing exertion cut off at the source to die as fading vapor above the heather while he peered back at the silent figure. She shifted, the hood of her cloak slipping from her cheek by way of the sea breeze and, at that movement, revealing to the wan light one watchful eye.Brown.So, not Eira herself then with her icy blue eyes. The clay figure had once been warm and sticky, and yet now it had grown almost cold and somewhat slick as if frozen in the wind, though he cradled it and its dwindled warmth so closely to his chest. He didn't give voice to his question, lungs filled only with breath enough for panting upon defeating the slope of the hill and a slight whine for the incessant pain beneath his bandage. He merely lifted an eyebrow, approaching slowly, or perhaps marching onwards. He still had his task, after all. He didn't fear the stranger—or perhaps more accurately he did not hold any more than the healthy fear anyone had for a stranger in those times and in that place. It wasn't uncommon to see the odd merchant trundle into town from this direction upon a tired old wagon, or to encounter a foreign sailor stopping over at the small port. But while the stranger was not Eira, neither did she seem to be either of those other things."What’cha got there?" the woman asked, an uptick of her chin shifting the opening of her hood even further back onto the crown of her head. In time with her words, there was a flash and a beep as something perched upon a dark brown tripod he'd nearly mistaken for a sapling swiveled to look at him. His steps ceased and wary eyes traced over the object that seemed a fey three-legged beast, staring at him with a single large glowing orb. Machinery, he realized after a moment. It had the same shiny, cold exterior and austere, utilitarian design as the things the sailors of iron ships sometimes brought. More such things were popping up here and there around the village each day. He turned his attention back to the woman after determining the machinery would be staying put upon those three legs."My sister," the boy asserted, holding out an open palm upon which that facsimile of mankind sat, the thing indeed closer in stature to that blue, lifeless bundle tossed into the sea than to either of them. He recalled with a lick of chapped lips the word the adults had used—the grumbling fishermen and hushed midwives. "Stillborn," he said.The woman leaned forward, one hand upon what he might have mistaken for a staff if he were still under any illusions as to her status as Eira, which was nothing but a small shovel. Her other strayed to her lips, a long drag blooming to life a little mote upon the ashy end of a cigarette. She studied his blood-infused handiwork for as long as it took for her to exhale a cloud of her own, made up of bitter, stinking smoke rather than the exertion of her heaving lungs as his had been. The last wisps of it curled from her nostrils as she drew her mouth into a thin line. Those brown, not blue, eyes flitted back up to him for a moment and a half before she spoke again."From the village, then?" she asked before quickly adding, "Of course you are." She seemed to have chosen not to remark upon the fact that a tiny clay doll that fit within a child's palm couldn't possibly be his sister, but whatever she did think of it was lost momentarily as her gaze fell to the bite her shovel had in the sandy dirt. It preceded how she rose, deepening that bite as she leveraged herself up with a huff and a tap of her cigarette. The boy took a half step back, clutching the little doll closer to his chest."That happen often?" the woman asked instead. "Stillbirths?" Her face turned aside, the cigarette pushed between her lips as the then freed hand reached out to fiddle with something upon the three-legged machinery. With a whirr it removed its gaze from the boy, returning to its idle attention down some grassy avenue that traced the ridgeline with a hefty click."No," the boy responded at first. He had survived after all, and that meant by necessity his mother had too, and he was sure that she had been born there. But how could he judge what 'often' really meant? "Yes," he decided. Though he had never done this ritual before, everyone knew how—knew someone who had done it too. "Maybe," he declared at last, giving up on the conundrum with a shrug. Some things had to be true—but whether it happened 'often' or not was not something he could determine. He was at least smart enough to know this fact.The woman only let forth a neutral hum, taking another drag of that cigarette as she began to take a few steps forward. They weren't directly towards him, but rather towards the line down which her machinery peered. To him she had at first appeared something otherworldly there upon the crest of the hill, and yet to her and her brown eyes that didn't even bother to look at him anymore, it was as if he were merely scenery as she went about her task. Perhaps that was not entirely true, however, for she did continue to speak to him as she stopped at her destination. "Won't have to worry about that soon," she stated matter-of-factly. "Though not soon enough, I'm sorry to say," she continued with a little nod in his direction, or rather to the doll he clutched and what it represented. "This railway will lead to the hospital at The University. And beyond. Carry you to and from quicker than a boat." She set the point of her small spade to the dirt, her boot giving it a solid kick to propel its wide point into the dirt. It seemed that 'often' to her meant 'at all.'What a railway was, or what a hospital or university was, the boy didn't know. Nor did he ask, though he found that he burned with curiosity at those new words. He had his task, and he found himself announcing to the woman, "I need to bury her," quite unbidden as he looked down to the doll in his palm. The woman didn't respond, merely shifting a few shovels full of dirt aside after glancing at him. She was digging a hole, no doubt, narrow in diameter but fairly deep. The displaced soil was placed in a small conical pile, darkened grains of minute earth beneath the top sandy layer tumbling slowly with each formation of a new peak brought about by another shovelful. No time for questions, though he burned. There was only grief and a curse to put to rest.As the boy began to walk past the woman and her strange business, however, she suddenly asked, "Is here fine?" She waved the head of her spade in a small circle about the narrow hole she'd dug out. The boy peered down into the neat circle cut out in the heath-speckled moor, the shadows filling it up like a well for its depth and the shallow angle of the sun that struggled to peek through gray clouds."We usually-" he began, thoughts turning from that artificial pit to the natural one. "-at the cave." He was muttering then, thought complete but not entirely spoken aloud as he conjured in his mind’s eye that dark furrow in the earth, currently out of sight but not often out of mind. The rend in the moor spiraled darkly downward, flanked by the limbs of a lacquered arch, maintained diligently but with the least possible exposure to that terrible, sacred place. They all knew it was not a place for village children to play—and not for the sharp, dripping rocks and complete absence of light beyond the first few steep steps inward, for mischievous brats never feared such things for all they were told to. It was for knowledge of its purpose: a maw meant to swallow up sacrifice and to return all that was owed to the veins of the earth. It wasn’t for the living.Usually.If his sister had survived, would she have one day been the chosen maiden, crippled for envy and suspended atop the gateway? He still remembered the lobsterman’s daughter. He remembered her skin fading sallow and the silent vigil, when his mother had shushed him in billowing skirts before he could finish asking why they wouldn’t help her down. Perhaps it was better that his sister had died then, before the sullen sacrifice and the festive feasting that had followed been declared necessary once more. But he would never, ever, say those words aloud."Why?" the woman asked, breaking through whatever deep rumination a scrawny child could muster in a brain made fuzzy by blood-loss and exertion of all flavors. The boy favored her with a look of confusion, though she’d already turned her attention to a satchel that hung at her side, the shovel thrust into the ground near the pile of exhumed dirt. His lips parted, ready to answer, though they stopped short of loosing more than a breath."I don't know," he found himself saying, despite the reasons they feared and respected that cave that he himself had thought of just moments ago. Perhaps it meant that, at that moment, those reasons weren’t enough for him, although this wasn’t something he would be prepared to ponder at length any time soon. "Why is Eira digging?" he asked in response. He called her that anyway, despite the fact that he’d already ruled out the possibility. He didn’t know her real name, after all, and it was rude to ask it rather than be given it. She didn’t seem to mind. It just seemed appropriate."This is where the rail line will go," she answered easily, crouching down to pat with a gloved hand the crumbling rim of the hole that threatened to chuck a loose tumble of dirt down into the space she’d just cleared. "The one that could have saved your sister." The boy found himself crouching beside her, peering into that miniature abyss. She’d chosen a good spot, one bereft of root, pebble, or worm. Only dark, loamy soil lined that shallow glimpse into the veins of the earth. She didn’t comment on what he had called her, whether she thought it a name or a title. Just another habit of those folks that lived by the sea, she might have thought."Will it help?" He asked at last. What exactly he was asking about, she didn’t question. Maybe he himself didn’t even know.The woman shrugged. "Won't hurt," she said simply. Her reasons, her answers, they were all like that. Simple. Reasonable. Rational.He held the figurine before him, thumb falling into the gap betwixt leg and arm. It was truly cold and stiff. It wasn’t in accordance with tradition—to bury the idol that bore Eira’s curse away from them all wherever he pleased. Despite this, he found that his hand had already disappeared up to the wrist into the hole she’d dug. Which was more important? Following the letter of the practice or the spirit? There was something about the wound in the earth this stranger had made that called to him, either way. The woman merely squatted beside him and watched silently until he’d laid the doll down and drawn his empty, bloodied, cold hand back out to rest it upon his knee.It was her turn to move, but rather than reach for her shovel she brought forth the object she’d withdrawn from her satchel earlier. Next to the clay doll, down in that small pit in the ridgeline, she nestled a little black rectangle. It too possessed that same outward appearance and those qualities as the tripod she had: smooth, sterile, and shiny. Only once it had been placed down inside did she take her shovel back up and begin filling in the dirt she’d displaced.She must have caught his inquisitive look, for she explained, “That’s how they’ll know where to lay the rail.” In short order she’d shifted all the soil back and patted it down with the back of her shovel, leaving not even a single hump where her strange device and his doll lay beneath, as if they had displaced no soil at all in their rest. “Your sister will be holding up a hundred-tonze locomotive.”It would perhaps have been more appropriate to say that a hundred-tonze locomotive would be driving over that burial spot, perhaps a few thousand tonze combined when considering each trailing car end-to-end, bearing down on the doll by way of a steel rail until it had been thoroughly compacted back into formless earth. The boy had no frame of reference for such a weight, but it did seem to him to be very, very considerable. Would any trace of his blood remain when finally that monstrous weight bore down upon the neatly filled in pit?“Sestia,” the woman said, holding out her hand clad in a dirty glove.He grasped it in the manner he saw merchants upon the docks do after purchasing a particularly large haul of dried fish, or even more often after a trade of saltwater pearls. They had brought the custom alongside their coins, marked with the face of their emperor that none of them had ever seen in person. He knew then whence she’d most likely come, and where the rail might ultimately lead. Her glove was rougher than it appeared, the microabrasions from handling the shovel, digging through dirt, and whatever other tasks this woman did making for a convincing facsimile of calloused palms. That palm and her fingers were cold, suffering not a single mote of heat to escape from within that layer of leather, nor a hint of the hanging chill to enter.“Noyel,” the boy responded. Perhaps that was what the handshake was for—the exchange of names. What else had been taken, or given, he was not yet prepared to say. Perhaps that made him a poor merchant, but then again it was a particularly poor day for haggling.

“We probably won’t meet again,” she said, nursing a small smile as she snuffed out her cigarette beneath a bootheel. It didn’t seem like it was out of some pretentious amusement for him, his sister, and their village rituals. Maybe it was more so that the pleasant distraction afforded by that chance encounter outweighed the net apathy of a single death of a stranger in a backwater village. She must have come a long way with her monotonous work, a silent tripod as her only companion, and she still had many more holes to dig. Perhaps she was mocking him though, and her purpose. He didn’t particularly care. Noyel’s attention had already turned away, the last vestiges of his tired consciousness lingering instead on whence she had come.At the end of a long rail-line, far past the boundaries of the furthest distance he could ever walk and still make it back home before nightfall with a scolding he could still survive, there would be a hospital. A university too. They were words strange and foreign, like the garb and hairstyles and complexions and coins and manners and speech of all those who came from afar to their port by boat. He never quite knew how the cogs cut through the uncertainty of the fog to bring news of monsters and the world at large, but waters are often made navigable by feelings and pacts with old men of the sea. Where those foreigners were seemingly disgorged as by magic by boat, the village’s connection to this hospital, and this university, would be as tangible as a spade striking the veins of the earth and a bloodied clay doll in the shape of mankind. If she had walked all this way, surely he could make the journey even more easily than she if her words held even the slightest hint of truth. Noyel turned away from Sestia and her task, cradling his empty hand to his chest once more.He began his climb back down the ridge.

The Greatest Knight

Theodemar’s battlefield instinct was perfect, his armored form on his caparisoned bird, having just wheeled to the rear for his squire to hand him a new lance, already ready to race ahead once more when his Captain began to press forward through the center of the enemy’s lines to break the vicious stalemate. His form was perfect, his back and the cantle as flawlessly enmeshed as his knees on either side of his steed, Warlord. His timing was perfect as he lowered his lance, the grapper sliding into the lance rest just under his armpit, the strain of holding the weapon before him delayed until, free of fatigue, his arm guided the killing-end towards his foe.The shatter of his lance was perfect, the break crisp and the spray of wood shards minimal when the front third broke inside the chest of the brigand he’d skewered, all the force transmitted to pierce his enemy’s chain shirt and leaving Theodemar with a wooden lance haft he could drop neatly as he rode on by. The way he slowed Warlord was perfect, the guidance of his knees and spurs all that was needed for an even deceleration when he neared the press. The way he smoothly drew his sword in one hand and raised his visor with the other was perfect, not a rattle or scrape to be heard from either. The sun was perfect, reflecting brilliantly off the tip of the shining blade in his fist and the brilliant smile on his face.His cry of, “Follow your Captain!” was perfect, loud and clear and sonorous and eliciting mirrored cheers not only from his own Lance but from all the mercenaries around him and even a warbling Warlord until he could feel their momentum bearing them along into the gap unopposed like a great tide. His first cut was perfect, the downward arc of his blade sending the edge straight through the battered shaft of a brigand’s spear to send it flying alongside the unfortunate man’s ear, before he raised his arm for another blow.The moment was perfect. Everything was perfect.Except his armor.Theodemar’s armor was good—very good—but it wasn’t perfect. No man’s armor could be perfect. It was simple physics. No fault of his own. He never saw the blow that felled him.The sudden and extreme drop in blood pressure stole his strength first, his bloodied sword dropping from numb fingers. It stole his vision next, the clear blue sky above dimming to a murky darkness as he listed backwards in the saddle. It stole his thoughts next, the unbridled joy of his moment of true knighthood, when he felt the strength of his armor, the fire in his blood, the thunder of Warlord’s pounding talons, and the courage of his comrades turning to utter confusion. Then it stole his breath and his consciousness and his heartbeat. He tumbled, tumbled, tumbled……Down into a pile of dirty straw.

It seemed to take him forever to rouse, the syrupy grasp of sleep yielding only reluctantly as the call of his name, repeated, breached the edge of his awareness at last. He groaned and stretched and ached. His body felt as though it had been asleep for ages, and yet between when he’d last closed his eyes and when he’d opened them seemed to have transpired in only a singular blink.His father smelled like shit. Theodomar knew he’d been digging in the latrine pits again, mucking and scraping and gathering any quality nightsoil to be carted off to Ul’dah, where it would be used to grow pumpkins for the Sultan. He was pretty certain that everyone knew it and could smell it. But it was nearly the only work available for a destitute refugee that couldn’t fight in the Foreign Brigades.Theodomar could barely remember the home he’d left by then, though it wasn’t that many years ago. Already the mountains of his memories’ Ala Mhigo were blurry and formless like melted clay. What he did remember, always remembered, and always would remember, however, were the Names. Kal'dur Thunderhead, Rudd Six-stones, The Bloody Smiler, and The Bleeder with his pet hunting hawk. He remembered their statues and their murals. He remembered each of the stories anyone had ever told of them and all the small squabbling over details that some contrarians and know-it-alls insisted upon forcing on everyone else. He remembered them all—all their tales of triumph and setbacks and bloody deeds.“There was a peddler that came by today,” his father said, breaking him from his reverie of thunder and blood. It was a rare, notable occurrence that anyone with more to sell than scams and drug-dreams stopped by any of the ragged seas of refugee tents, and Theodemar tried not to let the childish hope shine through in his eyes as he sat up and turned his gaze similarly upward. And for once in that desolate place the naive hope of the young paid off as his father announced, “-and I got something for you.” The object, which had fit neatly within his father’s curled fist, but seemed then to take up all of Theodomar’s palm as it was pressed from one to the other, was wrapped in a measly cloth. It kept it clean from the filth on his father’s hands. “It’s from a maker in Ul’dah, he said.” Theodemar hastily pulled away the ragged cloth, revealing the toy that had no doubt cost a sennight of shoveling—a figurine.It wasn’t one of the Named men. It wasn’t an Ala Mhigan at all, really. It was a knight on chocoboback, like one of the many slain by the score when thrown against the pike-wielding monks of King Manfred during the Autumn War. He knew them well. How the charge of the chocobo cavalry had made the very earth shake, how their brilliant pennants had become a sea of glimmering spear tips as they charged, and how they had killed and died. And ultimately triumphed over King Mandred’s dreams for an expanded Ala Mhigo. He’d always listened to those stories of war and glory too, around any fire from any mouth, young or old or bitter or admiring.The figurine was carved from wood and painted in garish colors, the fabric of the knight’s surcoat and the mount’s caparison lacking any texturing and the metal similarly lacking any semblance of illusionary shine. His father rustled his hair as he grinned at the foppish knight, and then laughed a rare, proud laugh to see his son’s glee. Theodemar examined every inch of it as his father departed soon after, who had realized that his boy’s attention was entirely on the gift. A victory, and they both were left smiling widely. It wasn’t the best craftsmanship, but it had the proper spirit, Theodemar had decided right away. There was a notch taken out of the edge of its pauldron by the whittling knife, the minute mistake covered with an extra thick dollop of paint, but he could still see the imperfection. But, to him, it was perfect. He held it tightly……But the first thing Theodemar noticed was that it made his hand hurt. Though the small figurine he clutched, the one he always wore around his neck with a bit of leather cord, was worn so smooth that it was half as big as it once was and almost featureless to the point where one could barely describe it as more than one blob astride another, he had been gripping it with a strength that left marks on the skin of his palm. That was strange. Where were his gauntlets? Why was he laying down?And then it all came back to him. The lance. His bird. His sword. The fall. His vision darted back to his hand, and he turned his palm over, counting each finger. Good. All there. Then he checked the other. Ten in total.He breathed a sigh of relief then, staring up at what he now realized was the infirmary tent from where he lay on a cot. He was aware that he’d been dosed with something for the pain, but it seemed to be handling whatever injury he’d sustained fairly well. He could barely feel a thing. Besides his hand.

It was when he tried to use his hips to swing his legs over the side so that he could get up that the trouble began. It had been a dull ache at first—a tingling numbness that soon became pins and needles. And yet needles became nails in a second. Nails became whole rail spikes the next. Fire danced along every nerve in his body as his stiff leg—heavily splinted, he realized vaguely somewhere within the tidal waves of agony suddenly washing over him—dropped off the side of the cot and hit the ground.He screamed.It summoned the Company chirurgeon on duty and, despite his agony, the worst sawbones in the camp, Goblin, was still the last person’s face Theodemar wanted to see. Though ‘seeing’ was relative when agony blurred his vision. The short, stubby, altogether too ugly man pushed the gasping, groaning Theodemar back onto the cot.“Peace, boyo,” Goblin croaked. “Not a good idea. Like to piss yerself from pain, and I ‘aint gonna be the one to change ya.” The chirurgeon tried to lift Theodemar’s splinted leg back onto the cot as gingerly as he could, but had elicited another ragged scream from the injured man by the time it was done. It was quieter this time at least, or more muffled, for Theodemar had turned his head aside, neck muscles straining, and screamed his agony straight into the thick sheet of canvas stretched over a frame that made up the cot he was on. It took many moments for him to tame the pain that left him feeling drained, and just when his psyche had gingerly begun exploring the jagged edges of what remained did Goblin tell him what happened.“One of them bastards found a gap in your armor,” Goblin grunted. “But those damn conjurers were nearby, Twelve bless ‘em. They went and closed all them ruined arteries. Saved your sorry hide, just seconds away from the big sleep.” Theodemar registered this supposed near-death experience with an appropriate amount of apparent apathy for as exhausted as he felt. They might have stemmed the flow of blood in time, but it would take more time still to replace what was lost. He felt sick, anemic. And there was still the question of his leg. Unable to muster a word, Theodemar just stared blankly at Goblin. He did manage to raise an eyebrow, the unspoken question delivered. It was when Goblin hesitated, eyes flitting to the wounded leg, and swept his tongue over his gray teeth that Theodemar began to worry. Goblin almost never hesitated to say whatever came to mind, no matter what it was. It was a quality that made him unpopular, and the opposite of part of what made Theodemar popular.“...But when you went down, you went down badly,” Goblin managed at last, gaze rising up to Theodemar’s for just a single second. “Your bird-” He paused, sucking in air through his teeth, and the gnawing dread in Theodemar’s stomach opened into a vast pit. “-Warlord.” Theodemar’s heart skipped a beat, though it had no business taking any breaks in his condition. Had something happened to his beloved mount? What was a knight without a steed? Warlord was the best he’d ever had—steadfast and loyal and always ready to brawl.